A PDF version is available here.

I found it really hard to believe that I hadn’t done Aberfeldy, the first masonry bridge I worked on. Long past time to remedy that before it is too late. I have had 5 weeks in hospital since 29th June. I am now on entirely palliative care, chiefly against infections. The cancer has to be left to run its course. I might yet manage to finish year 12 of this but it seems fairly unlikely.

Sorry about the finger. The chemotherapy has left me with debilitating peripheral neuropathy and even taking photos is harder than one hopes. This pic, taken on 21st June 2022 is the best upstream elevation I have.

The bridge, full title Wade’s Bridge Aberfeldy, was built in 1733, the crowning glory of the military road network built under General George Wade as part of a move to suppress the highlanders after the 1715 rising. There is rather more about the history and construction here.

At some point, the pronounced hump was eased by building up the approaches to be tangent to a rather larger radius hump. As a result, the parapets over the side spans are quite low. The “flat” top parapets through the main span make for a great height over the piers, certainly more than 2m at the highest. The picture below gives some impression of the height.

The string course in the foreground original also formed a kerb on the inside and marks the original road level. The present level is roughly where the parapet changes colour. A look over the crown from mid span provides an alternative view.

The dip in the string course is more pronounced than in the parapet top. The drop of the arch when the centres were removed was non-trivial. The parapets were not completed for nearly a year, so the sag there represents longer term movement.

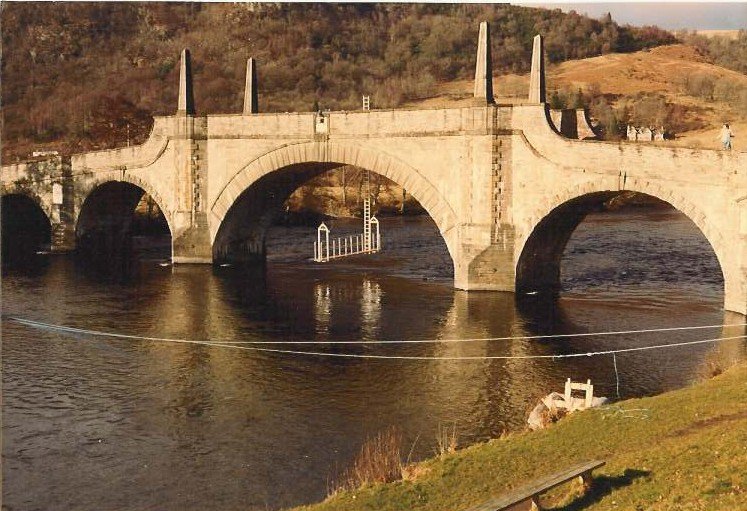

This picture from the 1980s shows the access scheme we devised for the early-stage monitoring. It had to represent a negligible restriction to traffic once in place but also the erection had to be accomplished during all the red time between traffic flowing in the two directions.

The monitoring was a response to the sudden imposition of a lot of heavy loads from a barytes mine. We estimated that some of the (notionally 40-tonne) trucks were loaded over 100 tonnes. The bridge was certainly shaken but no damage was evident and there was no measurable movement.

The nature of construction was clearer from close underneath. While the arch rings and spandrel walls were tight-fitting ashlar on the face, the central part of the arches was selected rubble with occasional larger stones. The closeups from the ‘80s are no longer accessible but modern long lenses can do well from the banks. Below is the main span where the dressed voussoirs extend some distance under the ring. Then rougher work has dropped markedly below the tight-fitting stones.

The wet patch is rather more trouble than it looks. An even longer lens from the opposite side shows that more clearly. That big stone looks to be on the point of falling out, though it may be anchored quite deep into the ring.

There is a similar patch diagonally opposite this one.

The wet patch is just about visible here at the ¼ span point. In one recent flood, the water reached this level. That will have sought out any weak mortar and removed it. Perhaps it was weakened by those heavy vehicles nearly forty years ago and the damage is only just showing. I certainly cannot imagine why the damage should be at diagonally opposite points in the span.

Perhaps you can see here how the parapet slopes out steeply through the bottom half of its height. The traffic lights require a cable over the bridge. The pitch intended to seal the slot for the cable broke down and water got in. Cycles of freeze thaw pushed the parapets out inexorably.

Back in 1981, I didn’t imagine I would still be so enthralled by masonry bridges at 75. It was a great pleasure to get back here and find it in basically sound condition.